Germanic cultures take Christmas cheer seriously. In Germany, Austria, and occasionally in neighboring countries, towns go so far as to have specialized Christmas markets, called Christkindlmarkt, which have been going on for centuries. At these frequently month-long festivals, you can buy (or just admire) all manner of traditional handicrafts. And of course, there are plenty of snacks. Selections often include sausages, marzipan, chocolates, and German-style mulled wine called glühwein. A similar Scandinavian mulled wine is called glogg.

Due to large-scale German immigration in the 19th Century, the tradition spread to the US, particularly Wisconsin. Many schools have holiday craft fairs, usually to raise money for various clubs and extracurricular activities, which bear a strong resemblance to Germanic Christmas markets. In my hometown, the two or three-dollar admission gets you access to dozens of local vendors, all set up in the high school commons and gym. Knitted hats, scarves, and mittens, painted wood and glass ornaments, creative jewelry, local honey and maple syrup, homemade jam, artisanal soaps and candles, bake sale treats, candied nuts, kettle corn, and all manner of decorations are available for purchase.

And don’t forget the lotion and lip balm. They’re great gifts because 1) they get used up and don’t add to “clutter” and 2) everyone can use them. When the heat gets turned on, everyone’s skin dries right out, especially the hands and lips. Almost every craft fair has a vendor selling these things, and they always do good business. Just make sure not to put scented soap and lotion in the same bag as your food, or the aroma will infuse. Eucalyptus-scented brownies aren’t for everyone.

For a more “authentic” European Christmas market experience, there are several options. I spent an enjoyable afternoon at one a few weeks ago and found some great treasures. It resembled a craft fair in some ways, but with more unusual and high-end merchandise. One memorable stand had ostentatious fur hats, made of fox, coyote, wolf, racoon, skunk, and rabbit. They were pretty flamboyant and definitely out of my budget, but fun to look at. Other stands had unique maps, Baltic amber, alpaca wool socks, scarves, and hats, hand-painted wooden nesting dolls, German beer steins, and of course, all sorts of food.

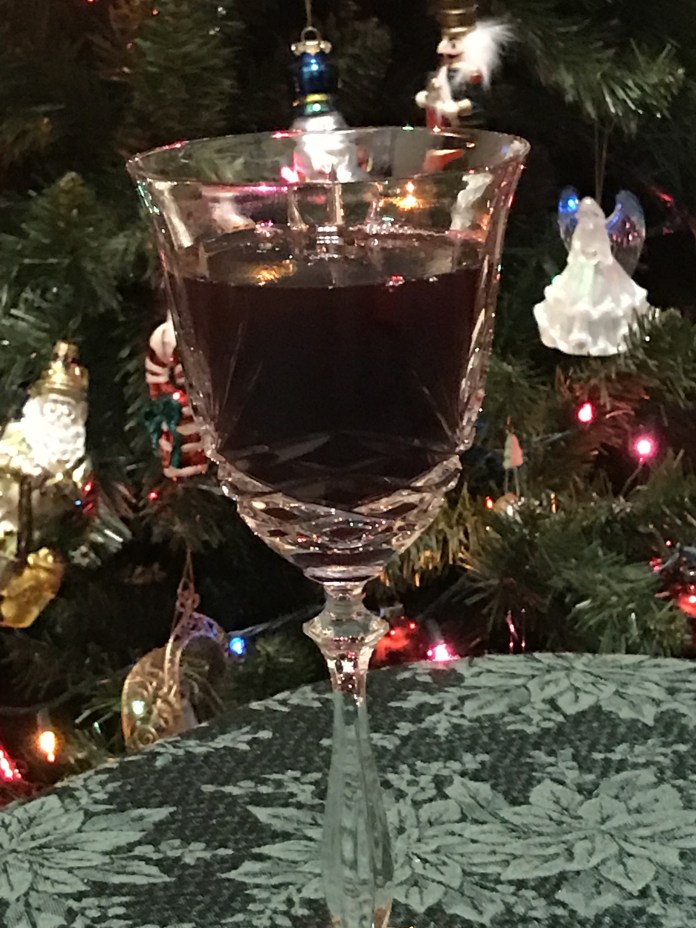

Just like in Germany and Austria, the market in Wisconsin served up sausages, schnitzel sandwiches, little spätzle dumplings, red cabbage, and amazing potato pancakes. I definitely need to master making them at home. Desserts included apple strudel and crepe-like German pancakes, homemade cookies and bars, tins of Scandinavian-style gingersnaps and cardamom cookies, and all sorts of European chocolates. To wash everything down, there was a variety of beer and wine, including, naturally, hot glühwein.

After purchasing a few “winter survival” lotion/lip balm kits, I loaded up on edible treasures. Between the toffee, cardamom cookies, and fabulous 2-year aged cheddar, a trip or two to the gym might be in order. Really, that’s a good idea anyway. The more time spent watching documentaries while on the elliptical, the more Christmas treats you can enjoy.