Despite his remarkable career, Napoleon Bonaparte had several close calls on his rise to power. One such case was at the Battle of Marengo in June 1800. Napoleon had seized power in a coup the previous year. To secure his rule, he needed military victories. At the time, he was fighting the Austrians for control of northern Italy. They met in battle near the city of Alessandria, in the Piedmont region.

At first, the battle didn’t go well for the French, but Napoleon managed to snatch victory from the jaws of defeat. His control over Italy was secured, skeptics in France were reassured, and other ambitious generals were discouraged from turning on him. To celebrate, or simply because he was hungry after a long and no doubt stressful battle, Napoleon requested a special dish. Or so the story goes.

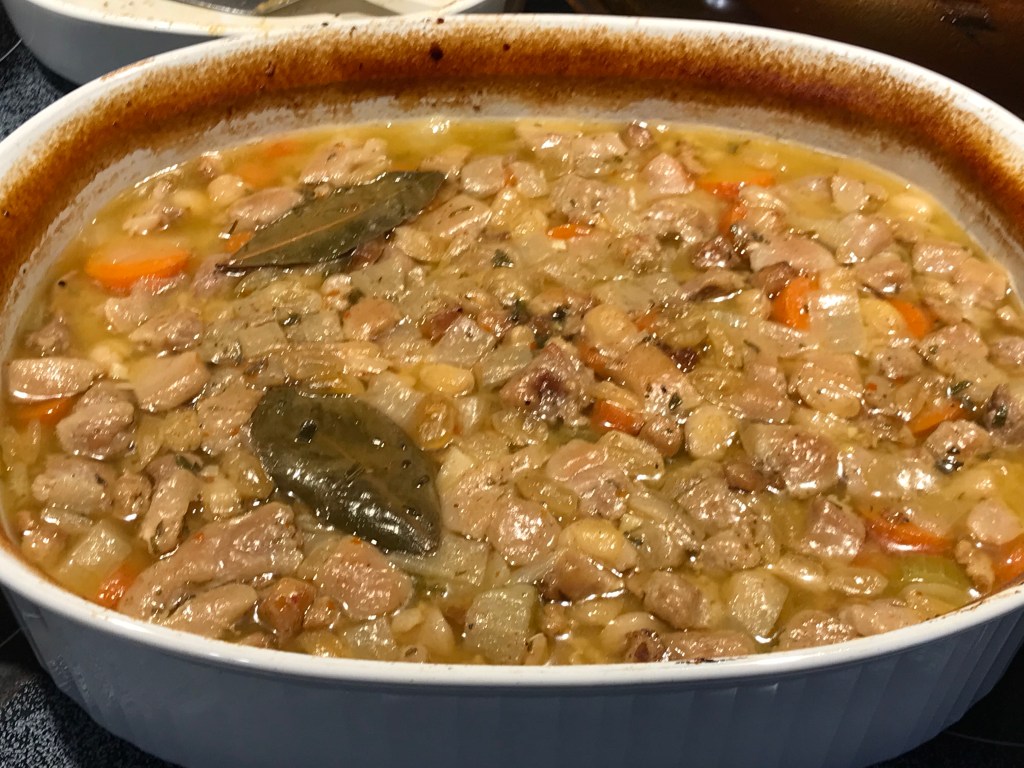

Recipes for chicken marengo vary enormously. The only constants seem to be chicken (or occasionally veal) browned in olive oil, onions, and tomatoes, braised together to make a sort of stew. There’s usually garlic, mushrooms, and white wine. Many recipes include shallots and parsley, and a few use brandy instead of wine. Great chef Auguste Escoffier recommended including fried eggs and crayfish. Regardless of specifics, toasts fried in butter traditionally accompany chicken marengo.

To make things even more complicated, there seems to be a debate about whether chicken marengo is French or Italian. In Mimi Sheraton’s 1,000 Foods to Eat Before You Die, it’s in the French section, but I’ve also seen recipes in Italian cookbooks. Since the Piedmont region was historically part of the Duchy of Savoy, a realm straddling the Alps between France and Italy and right on the trade routes between them, it’s hardly surprising that a Piedmontese dish would be adopted into French cuisine, or vice-versa. And it’s fitting that an entrée associated with Napoleon should be considered both French and Italian. After all, he himself was a native of Corsica, then ruled by Genoa, but made his career in France.

For my own recipe, I combined the different strands into one, with no eggs or crayfish. The nice thing about chicken or “veal” marengo is that after browning the meat and making the “sauce,” it can be kept overnight and cooked the following day. Everything can be done in a Dutch oven, but if you don’t have one, a skillet and slow-cooker will also work. If you want to reduce fat and calories, the bread can be toasted dry in the oven or toaster, instead of in the buttered skillet. Or don’t toast it, if you prefer, but whatever you do, don’t skip it. You need bread to soak up the sauce.

Here’s how to make it:

Ingredients:

- 1 chicken, cut up, or roughly 3 pounds bone-in pork (or veal) chops

- 2 tablespoons olive oil

- 4 tablespoons butter, plus more to brown toasts

- 1 medium onion, quartered and thinly sliced

- 2 shallots, halved and thinly sliced

- 4 garlic cloves, crushed with the side of the knife and minced

- 1 bunch parsley, thick stems separated from leaves and thinner stems, and both parts minced separately (don’t discard the thick stems)

- 3 tablespoons dry white wine, mixed with 1 tablespoon brandy

- 2 tablespoons flour

- 1 (roughly 15 oz) can crushed tomatoes, or about 2 lbs fresh tomatoes, chopped

- 1 pound mushrooms, cut into thick slices, with larger pieces halved

- Baguette or Italian bread, to serve

Directions:

- Brown meat in the olive oil and two tablespoons of the butter in the skillet or Dutch oven over medium heat. Set aside on a plate.

- Add onion and shallots and sauté, stirring frequently, for about 5 minutes, or until they start to turn golden. Add the garlic and parsley stems and cook for 2 more minutes (garlic is added later because it cooks faster and burns more easily).

- Stir in the wine/brandy mix, making sure to scrape up any browned bits at the bottom of the pan. Cook until the liquid is mostly evaporated, 5 to 10 minutes.

- Add the flour and stir until incorporated. Follow with the tomatoes, and water if using canned. Bring sauce mixture to a boil. If using fresh tomatoes, reduce heat and simmer for 10 to 15 minutes, until the tomatoes break down and release their juice. Add salt and pepper to taste.

- Place the meat, skin side up if using chicken, in the Dutch oven or slow-cooker, and cover with the sauce. At this point, the chicken/pork/veal marengo can be refrigerated overnight if desired.

- Preheat oven to 325 degrees Fahrenheit, if using Dutch oven. Bake for 2 to 3 hours, until the meat is tender (if the stew was chilled overnight, it will probably be at the longer end of the time range).

- If using a slow-cooker, cook for about 4 hours on high or 6 – 8 on low. If it’s a little longer, like if you put it on before leaving for work, that’s completely fine.

- Half an hour before serving (with either cooking method), melt the remaining butter in a skillet over medium heat. Add the mushrooms and a little salt and cook, stirring frequently, until soft and aromatic, about 10 to 15 minutes. Add to the stew, pressing them down into the sauce, and leave to cook while browning the toasts (or for 15 minutes if you decide to use untoasted bread).

- Toast the bread pieces in a buttered skillet over medium low heat until browned.

- Sprinkle the stew with the parsley leaves and serve, toasts on the side.

And as always, please like, subscribe, and/or share to support my work.

Make a one-time donation

Make a monthly donation

Make a yearly donation

Choose an amount

Or enter a custom amount

Your contribution is appreciated.

Your contribution is appreciated.

Your contribution is appreciated.

DonateDonate monthlyDonate yearly