By European standards, France is a large country. As with any nation with varied terrain and climate, it has a number of regional specialties. There are the dairy-heavy cuisines of Normandy and Brittany, Germanic-inspired dishes of Alsace in the northeast, and wine-based sauces and stews from the wine-growing regions of Burgundy and Bordeaux. And in the south, along the Mediterranean, is Provence, where many dishes resemble those from neighboring Liguria in Italy.

Provence is one of the few French regions where olive trees can produce fruit. The oil is ubiquitous, including in a sauce for roasted eggplant. Other Mediterranean flavors come from lemon juice, capers, and a bit of anchovy. Before you get grossed out, it’s just a small amount of paste used as a flavor booster, not enough to make it taste “fishy.” All these other flavors, which are rather strong on their own, plus garlic and plenty of fresh parsley, balance it out.

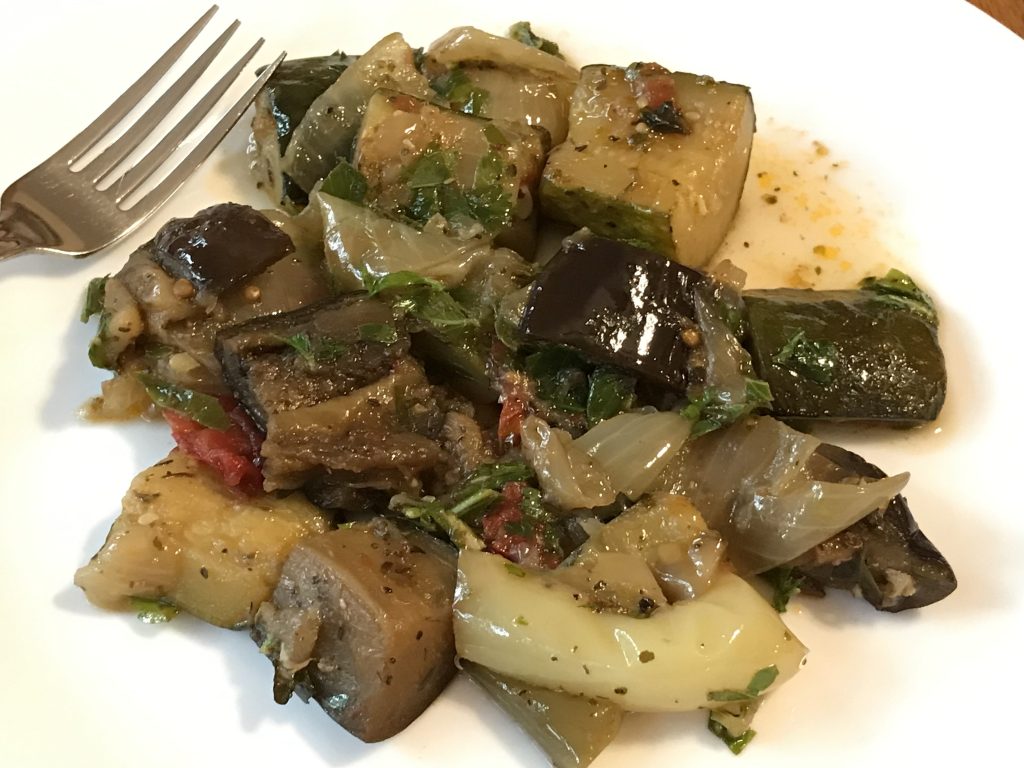

Aubergine is the French word for eggplant. Here it is cooked and pureed just like in baba ghanoush, except in the oven instead of over a wood fire, producing a lighter color and mild, slightly sweet flavor. Rather than mixed into the puree, the sauce is served over the top, for a greater contrast.

As Mimi Sheraton suggested in 1000 Foods to Eat Before You Die on page 54, a simple description is sufficient to compose a recipe, at least for the sauce. It was the eggplant itself that gave me trouble. When cooking whole, which is necessary to keep the pulp a greenish color instead of browning, it takes a surprisingly long time to soften. At 400 degrees Fahrenheit (or just under 205 degrees Celsius), it took nearly an hour. Since it was a cool day that was fine, but on a hot summer day that would never be an option. Plus, using the oven for that long for one fairly small item doesn’t seem energy efficient.

I considered ways to “pre-cook” the eggplant before finishing it off in the oven. After poking holes all over (to release steam and avoid an explosion), boiling or steaming would probably introduce too much water. But what about the microwave? They work by making water molecules move faster, creating friction and raising the temperature. And since the rays pass through the food, the center warms up much faster than with other cooking methods.

For a vegetable like eggplant, which has a high water content, this worked like a charm. To avoid an explosion and mess, I poked the holes all the way through with the pointy end of a meat thermometer, giving plenty of openings for steam to escape. Just heat on a microwave safe plate, turn every two minutes, and be careful when handling. The eggplant steams inside the skin, creating the perfect silky texture with just the right amount of moisture.

As it turned out, the oven wasn’t even required, making this interesting dish perfect for a hot day. When the eggplant is cool enough to handle, just cut in half, scoop out the pulp, puree it, and serve warm or at room temperature with the sauce. Accompany with bread, crackers, or crunchy vegetables.

The sauce recipe is easy to double and can be kept in the refrigerator for several days. Don’t worry if the oil solidifies; it will turn liquid again as it warms up. This is common for vinaigrette-type dressings and sauces. Just get them out of the fridge half an hour to an hour or so before using, and they’ll be fine.

Ingredients:

- 1 large eggplant, about 2 pounds

- 3 tablespoons olive oil

- Juice from ½ lemon

- 1 clove garlic, minced

- 2 tablespoons capers, minced

- ¼ teaspoon anchovy paste

- ½ bunch parsley, minced

- Salt to taste

Directions:

- Combine all ingredients except eggplant, parsley, and salt in a bowl and whisk to dissolve anchovy paste and combine.

- Whisk in the parsley and taste for salt. The anchovy paste and capers are both salty, so you might not need it.

- Set sauce aside at room temperature, or refrigerate overnight. Bring to room temperature before serving.

- Poke holes all over the eggplant, all the way through. Place on a microwave-safe plate and cover with a paper towel. Microwave on high for 8 to 10 minutes, turning every 2 minutes, until a skewer slides easily into the flesh. Let rest until cool enough to handle.

- Cut eggplant in half and scoop flesh into bowl of a food processor. Process until smooth.

- Scoop eggplant puree onto a plate, spoon sauce over, and serve with bread, raw vegetables, and/or crackers.

For more recipes and food history, sent right to your inbox, please like, subscribe, and/or share.

Make a one-time donation

Make a monthly donation

Make a yearly donation

Choose an amount

Or enter a custom amount

Your contribution is appreciated.

Your contribution is appreciated.

Your contribution is appreciated.

DonateDonate monthlyDonate yearly