Variants of chicken soup are eaten all over the world. Flavorings might vary, but the concept seems to be pretty universal for non-vegetarians. Historically, this usually involved a rooster or hen past their mating or egg-laying prime. Tough but flavorful, the chicken would be slow-cooked in liquid to tenderize the meat and produce a rich broth.

One Belgian recipe, called Waterzooi a la Gantoise, involves stewing the chicken with leeks, celery, and parsley root or parsnips, flavoring the mixture with lemon and cream, and thickening it with beaten egg yolks. Odd as this mix might sound, the recipe from 1000 Foods to Eat Before You Die, pages 151 – 152, had a nice flavor.

Belgium has a long and complicated history. Composed of Dutch-speaking Flanders and French-speaking Wallonia, it was a battleground between France and the Holy Roman Empire for centuries. During the Middle Ages, Flanders in particular grew wealthy from cloth production. Since they needed English wool, attempts by the French kings to shut down the trade during their many conflicts with England predictably let to unrest. So did the kings’ attempts to centralize power in general and levy taxes.

In the late 14th Century, most of the Low Countries came under control of the Dukes of Burgundy, followed by the Habsburgs a hundred years later. Charles V, the most powerful Holy Roman Emperor in centuries, was born in Flanders in 1500. By the time of his retirement in 1556, his empire included Spain, the Low Countries, Austria, Naples, Sicily, Milan, and Spain’s growing New World empire. All except Austria and the imperial title itself went to his son Philip II. Charles V’s brother Ferdinand I, who had been his deputy in Austria for years and gained Bohemia and Hungary through marriage, received these, creating the Habsburgs’ Austrian branch.

Just the Spanish Habsburg territories were a monumental task to control, as Philip II soon found out. He was hardworking but struggled to delegate, which made managing the far-flung provinces difficult. A particular issue was the spread of the Reformation in the Netherlands. Philip was not inclined to compromise on matters of religion, and unlike his father, didn’t spend much time outside of Spain after taking the throne. Feeling alienated by a “foreign” ruler, the Dutch revolted in the 1560s, leading to Eighty Years’ War. They were aided by England, which was part of why Philip sent the Spanish Armada.

When the dust settled, the modern Netherlands became independent, while modern Belgium remained part of the Spanish Empire. It was transferred to the Austrian Habsburgs in 1714, after the War of the Spanish Succession, and became part of the Revolutionary French Empire in the 1790s. After the defeat of Napoleon, Belgium was ruled by the restored Dutch monarchy. A few decades later, Belgium became independent under Leopold I, an uncle of Queen Victoria.

After everything they went through, Belgium tried to remain neutral in the 19th and 20th Centuries. With British support, this worked until 1914. When World War 1 broke out, Belgium had a problem. Specifically, Germany’s war plans. Since German high command knew they would be fighting on two fronts, they sought to defeat France quickly, before Russia managed to mobilize its army. The issue was that the French-German border was heavily fortified. The idea, called the Schlieffen Plan, was to go around these defenses by invading through neutral Belgium.

When Belgium refused military access, Germany declared war on them. Belgian forces put up a tougher fight than expected, giving the French time to reorganize their defense and for British support to land. By December, the Western Front was more or less stabilized, running right through Flanders, where it would remain for roughly three-and-a-half years.

The initial German advance, the years of occupation, and the eventual retreat in 1918 did a number of Belgium, especially Flanders. Attempts to stay neutral during World War 2 also failed, resulting in another multi-year occupation. Afterwards, finally, Belgium has finally enjoyed several decades of peace.

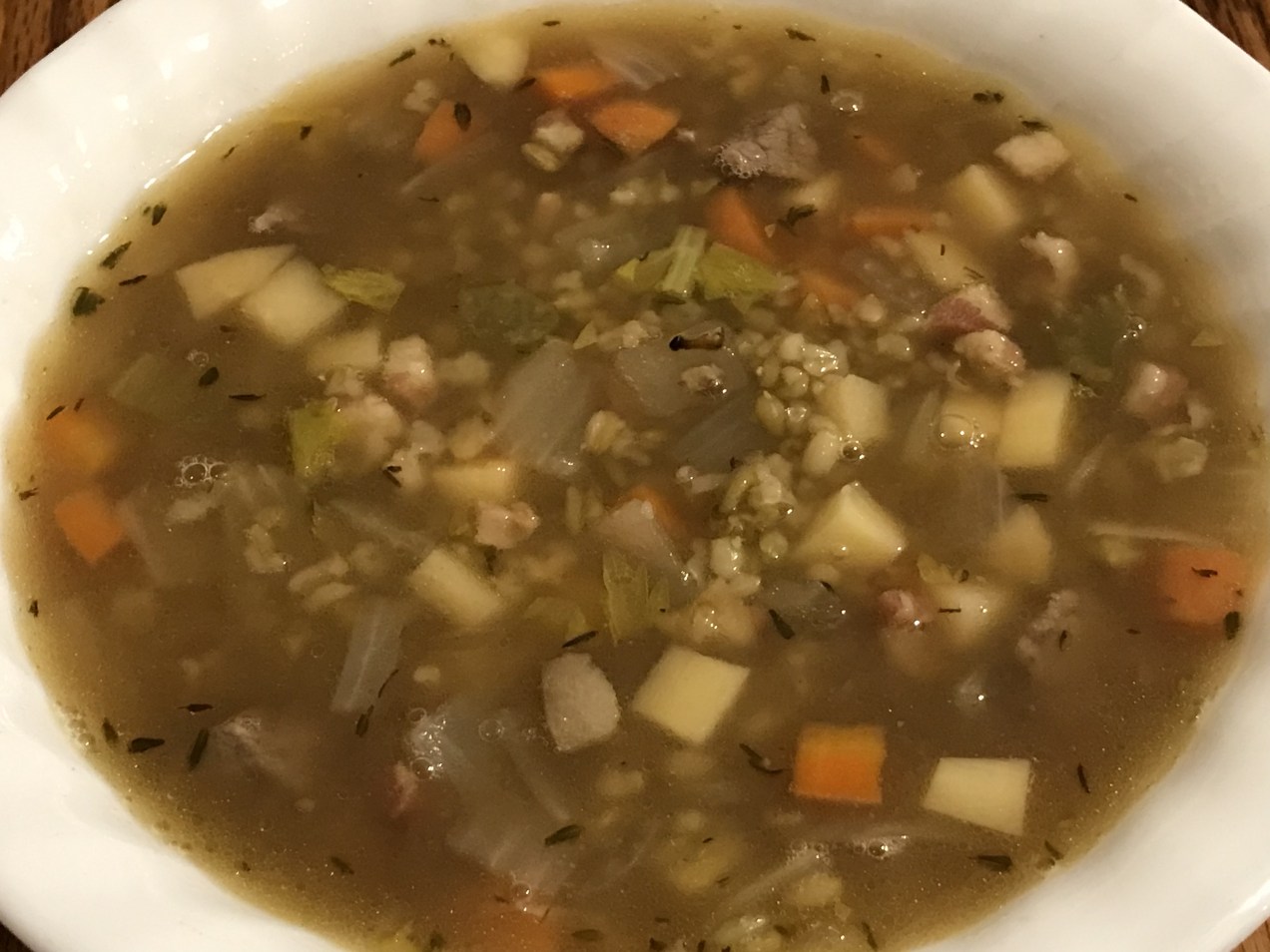

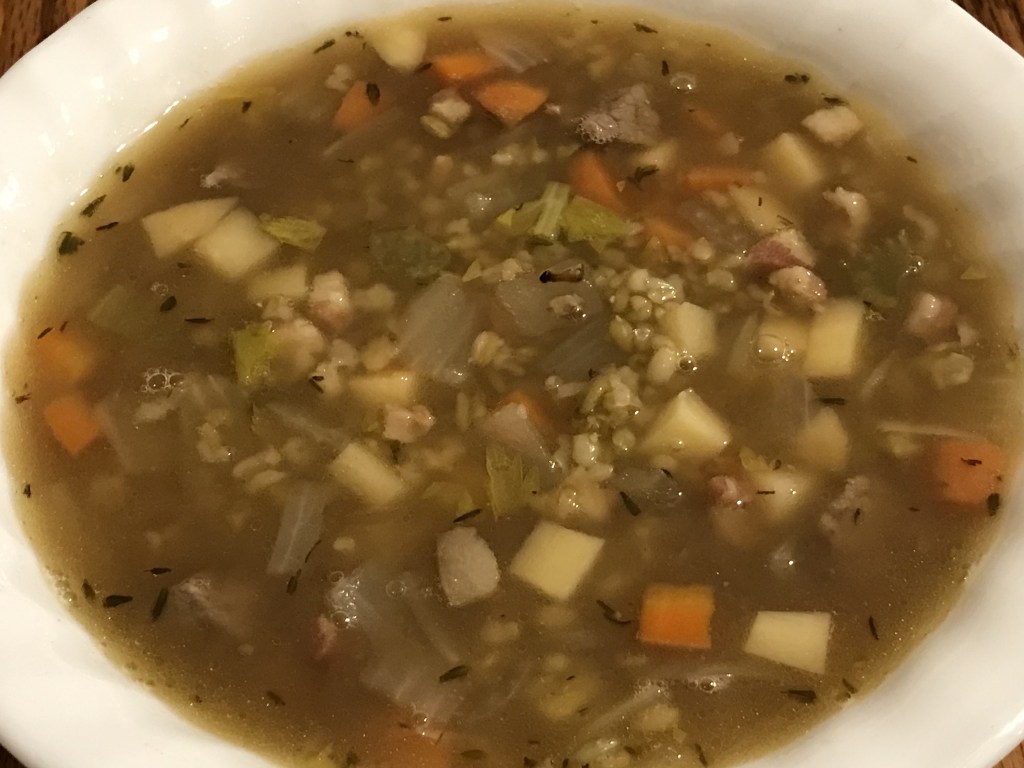

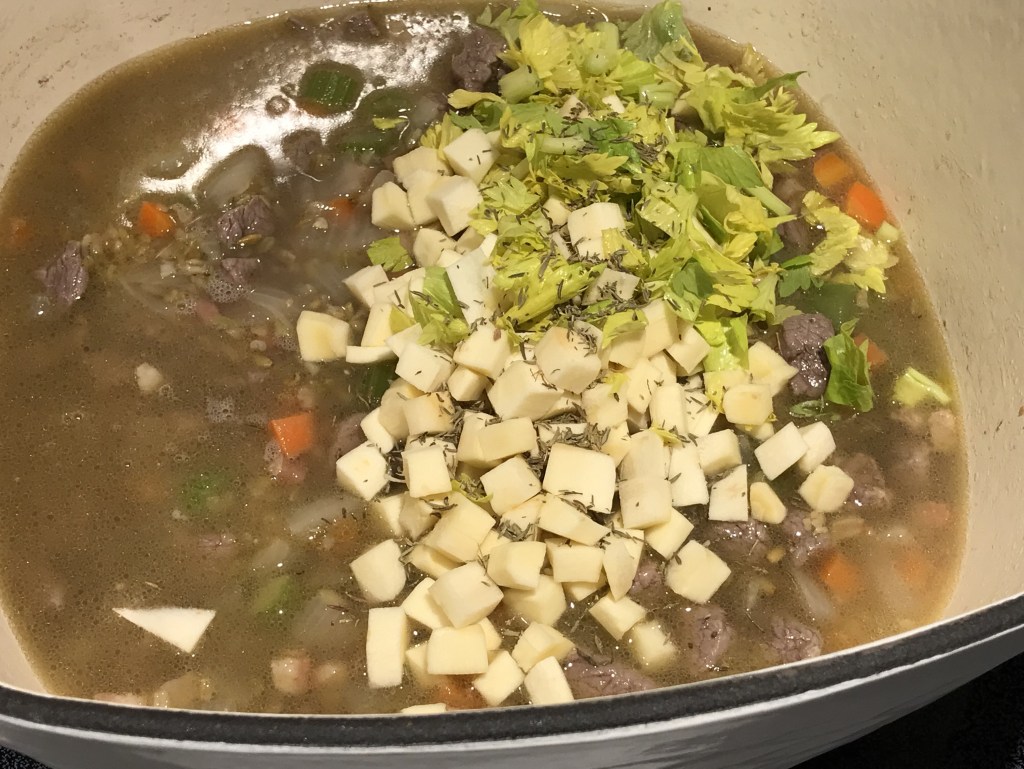

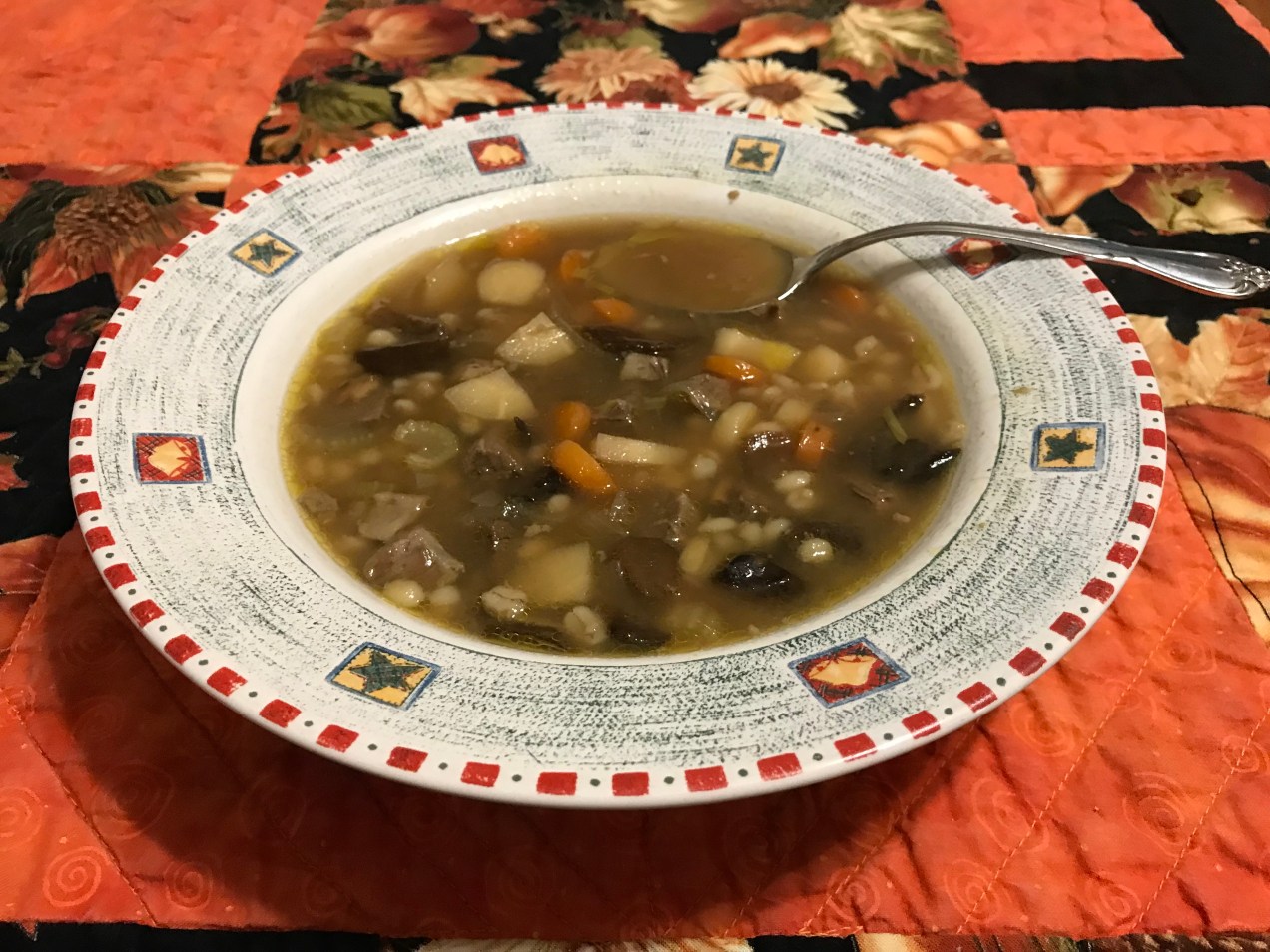

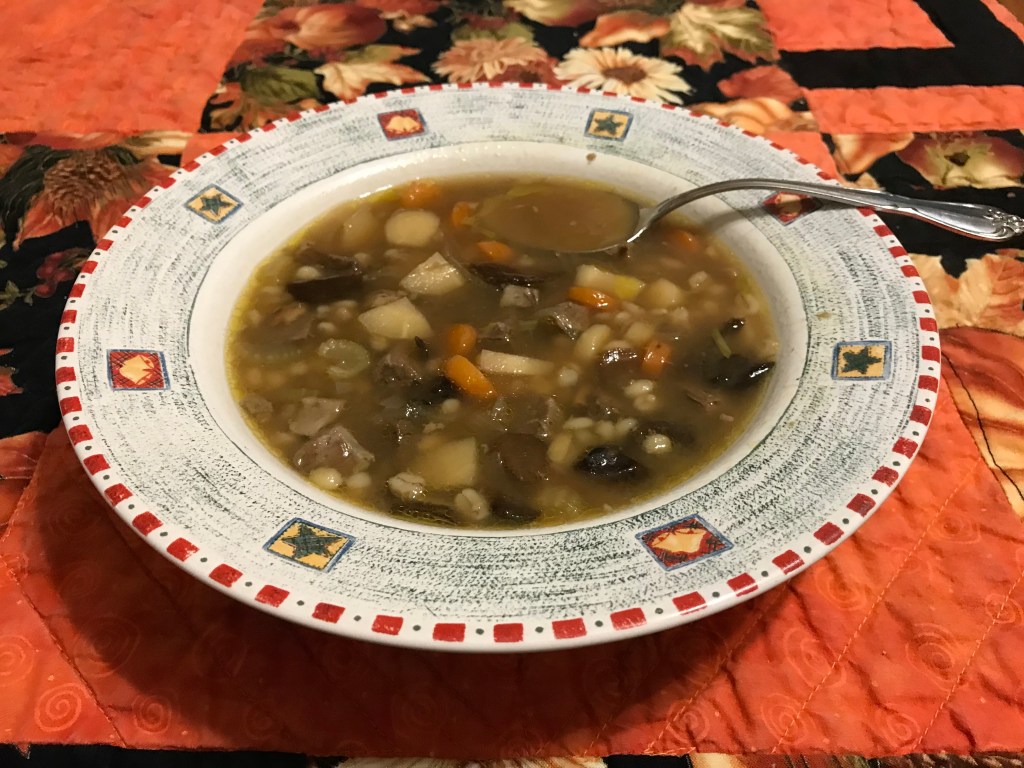

Evidence of prosperity can be seen the soup recipe, which uses chicken, eggs, cream, and vegetables that are not ultimately eaten. Since using vegetables to flavor the stock but then discarding them offends my sensibilities, I ended up returning them to the pot after removing the chicken skin and bones and straining the broth. The celery and leeks were a little overcooked, but still added some nice extra texture to the soup.

Immediately before serving, some of the hot broth is whisked into the egg yolks to temper them, then the mixture is returned to the pot to thoroughly heat but not boil. This is the same technique used in making custard, but for some reason the waterzooi didn’t thicken as much as I anticipated. Maybe I used too much water (the recipe said just enough to cover the chicken, which I thought I did). Maybe I didn’t heat the soup long enough after adding the egg yolks for fear of them curdling. Or maybe the issue was my expectations. Custards thickened with egg alone and not boosted with cornstarch are very thin.

Overall, the soup was very good, but not necessarily worth the trouble of making again as is. Perhaps pureeing the slightly overcooked vegetables into the broth as additional thickening would give it some extra body. (An immersion blender would be great for this.) On a scale of 1 to 10, I would probably give it a 7.