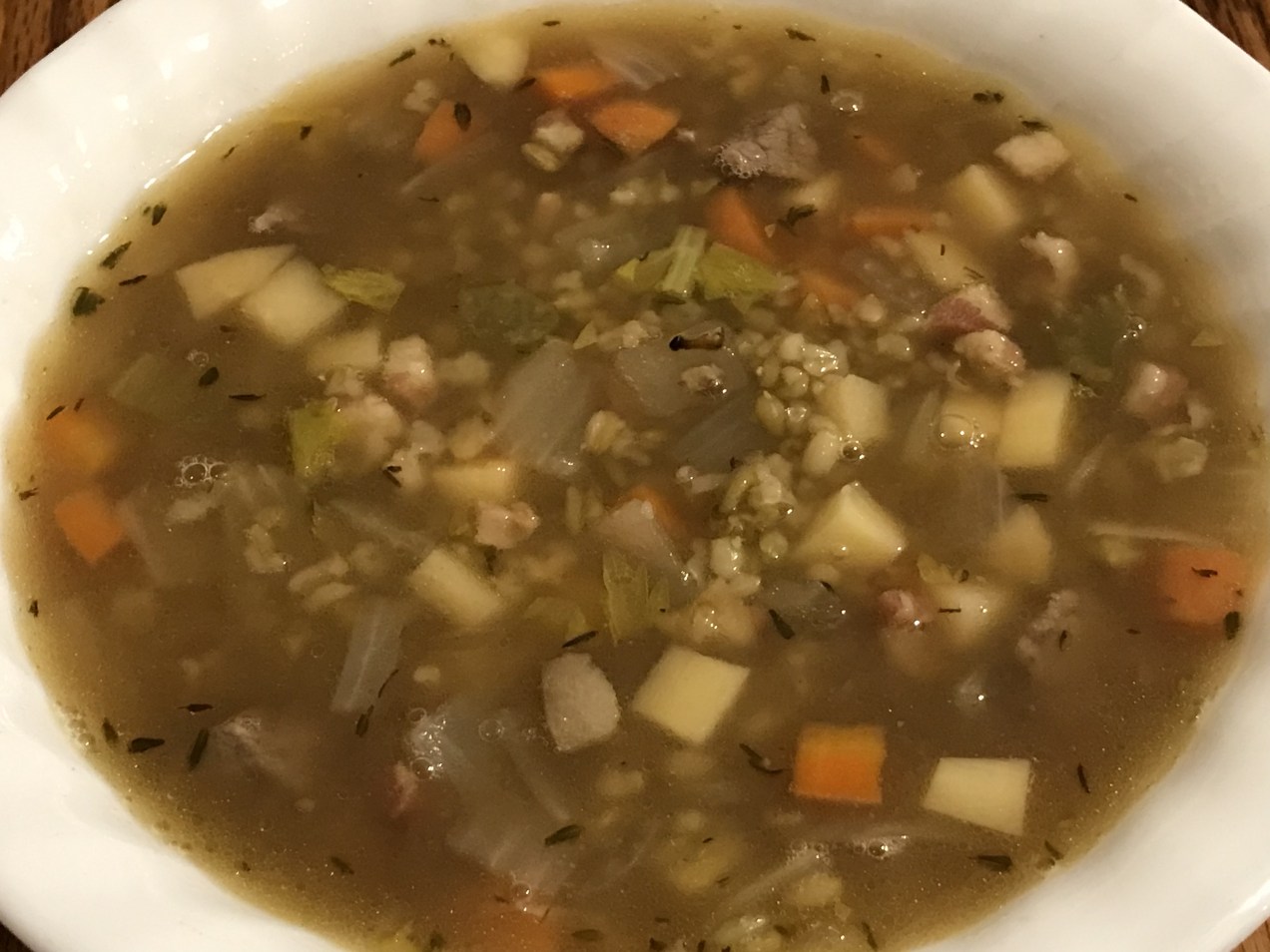

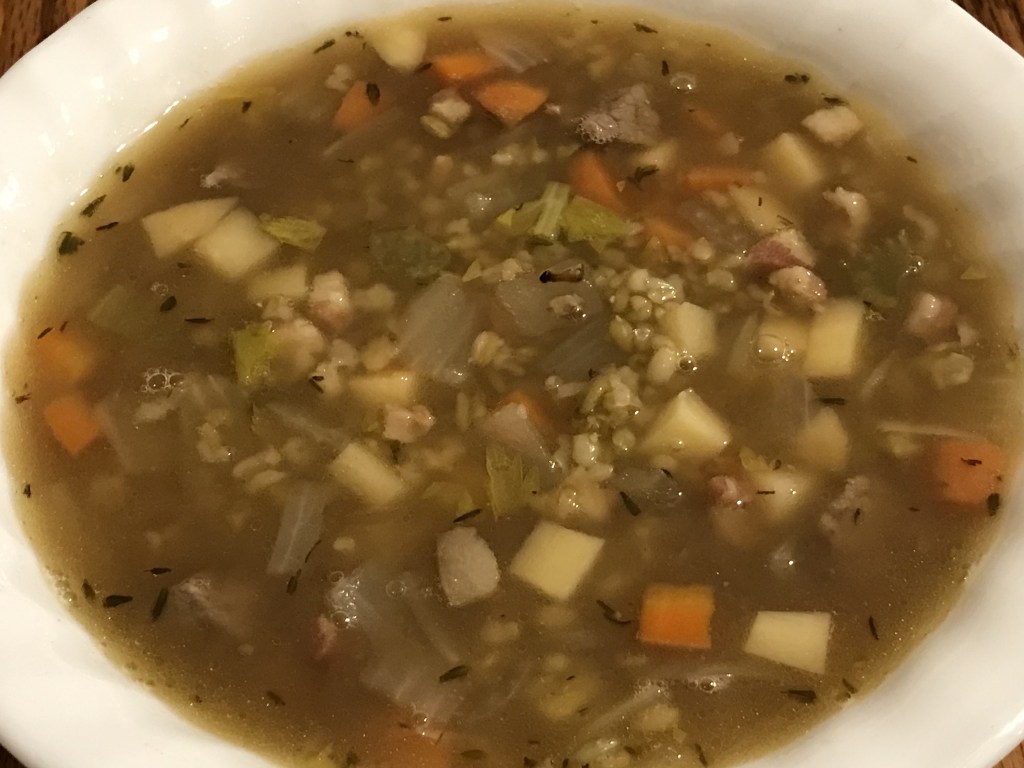

If asked to name a Hungarian dish, goulash is probably what most people would come up with first. And that isn’t a bad thing. It’s flavorful, soothing, and endlessly customizable. Plus, like most stews, it reheats extremely well. For Sunday dinner with leftovers for lunches, it’s perfect.

According to Mimi Sheraton in 1000 Foods to Eat Before You Die, goulash was originally a cowboys’ stew. Beef is the most common meat, but pork is also widely used. Since pork is typically half the cost of beef or less, and makes excellent goulash, that is what I use in the recipe, though beef cubes will also work.

The critical ingredient is paprika, which is actually a relative newcomer to Hungarian cuisine. It is made of dried and ground peppers, which originally came from the Americas. Most likely, peppers arrived in Hungary during the reign of Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, whose empire included Spain, the Low Countries, parts of Italy, Austria, Bohemia, and Hungary, though it took a few centuries for Europeans to accept them.

By the 19th Century, paprika was a central flavor in Hungarian cuisine, and indispensable in goulash. Besides the meat (or occasionally beans) and paprika, other ingredients might include onions, garlic, potatoes, carrots, tomatoes, or green peppers. In other words, the usual suspects in stew. Some versions include caraway seeds, sage, sauerkraut, or even grated apple.

For my version, I settled on all the usual suspects except green pepper, for the simple reason that it was the only one I didn’t have on hand, needing to be used up. That’s one of the nice things about goulash. The ingredients are affordable, easy to find, and often already in the kitchen. Caraway and sage add a nice extra flavor, and a bit of apple cider vinegar brightens everything up. If using fresh tomatoes, don’t worry about peeling or seeding them. With the long cooking time, they break down into the broth, leaving just their flavor, vitamins, and lovely red color.

Ingredients:

- 4 pounds pork butt, shoulder, or assorted bone-in chops

- 2 onions, chopped

- 2 garlic cloves, minced

- 8 ounces carrots, sliced

- 4 tablespoons (¼ cup) unsmoked sweet paprika (This is not a typo. It sounds like a lot, but goulash is supposed to be very paprika-forward, not subtle.)

- 1 tablespoon caraway seeds, lightly crushed

- Dash cayenne pepper

- 2 pounds fresh chopped tomatoes (about 7 – 8 Roma tomatoes), or 1 15-ounce can crushed tomatoes and 1 can of water

- 6 small red or gold potatoes, unpeeled, cut into roughly ¾ inch cubes

- 8 sage leaves, thinly sliced

- 1 tablespoon apple cider vinegar

Directions:

- Trim the extra fat from the pork, mince it, and cook over medium heat until it’s mostly melted and rendered.

- Cut as much meat from the bones as you can, cut into roughly ¾ inch cubes, and set aside the meaty bones.

- Add the pork cubes and bones to the fat and cook over medium heat, stirring occasionally, until most of the pink is gone and the remaining fat has begun to render, about 10 minutes.

- Add the onions, garlic, carrots, paprika, and caraway, with salt and a dash of cayenne pepper. Cook roughly 10 more minutes, until the onions start to cook down.

- Add the tomatoes (and water if using canned) and cook for another 10 minutes.

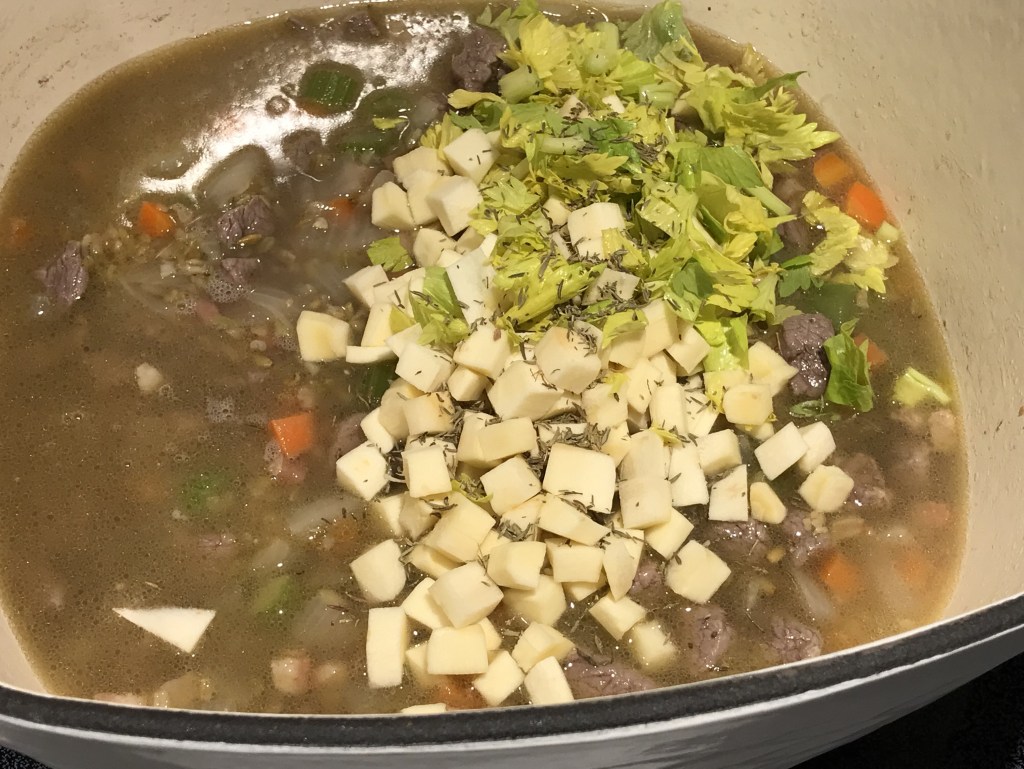

- Reduce heat to simmer. Add the potatoes and sage leaves, cover the pot, and cook until everything is tender, ½ hour to an hour.

- Remove the bones, pull any pork from them, and return the meat to the pot. Discard the bones.

- Immediately before serving, stir in the vinegar. Serve alone or with mashed potatoes, egg noodles, dumplings, or bread.

Rating: 9/10

For more recipes and fun facts, make sure to subscribe for free. Of course, any contributions to buy more pork chops would make me very happy.

Make a one-time donation

Make a monthly donation

Make a yearly donation

Choose an amount

Or enter a custom amount

Your contribution is appreciated.

Your contribution is appreciated.

Your contribution is appreciated.

DonateDonate monthlyDonate yearly