Every fall, I bring my potted herb plants in from outside to enjoy using them for a bit longer. It works well enough for a while, but eventually they start to suffer from the limited sunshine. Since most of them are annuals, the time comes to use up what I can before starting again when summer returns. Everything except the rosemary is either done or fading. To use up as much as possible, I made a French classic, omelette aux fines herbes.

Fines herbes is a mix of parsley, chives, tarragon, and chervil, common in French cuisine. The first three are widely available in the US, but chervil might require a specialty spice store or the internet. Supposedly it tastes like a milder parsley with a bit of a licorice undertone, but I couldn’t taste much difference. To compensate for all the herbs except parsley being dried, I also added some minced scallions to brighten things up.

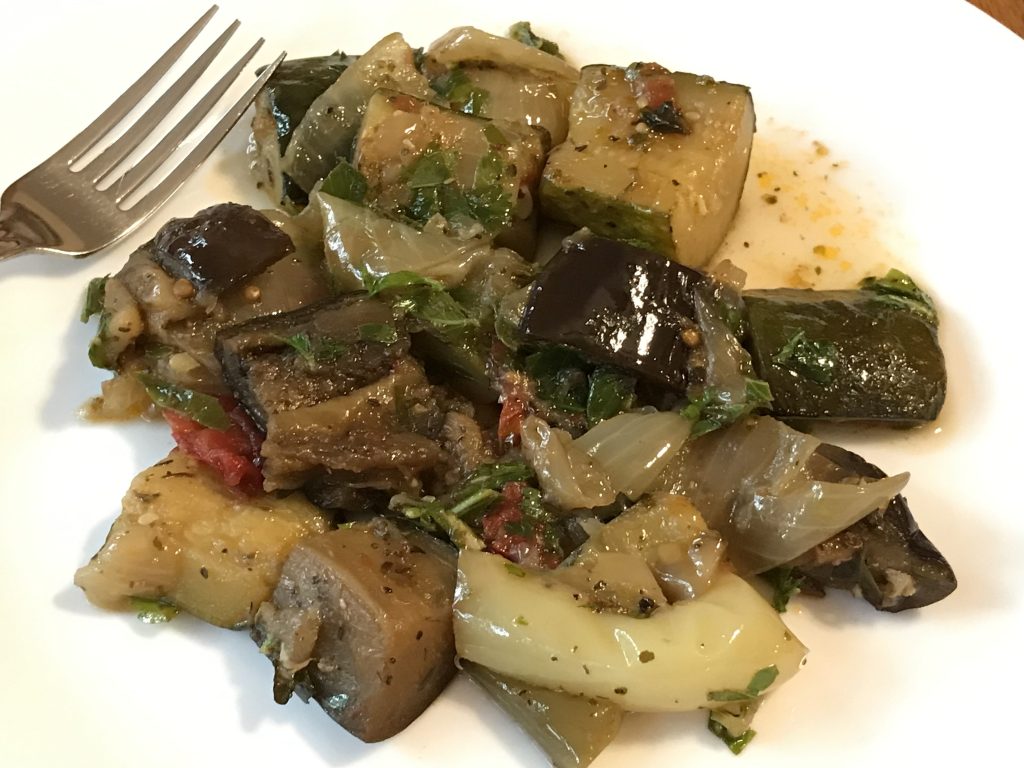

For many French chefs, making a perfect omelet is one of the primary tests of skill. After following the basic directions on pages 107 – 108 of 1000 Foods to Eat Before You Die, mine turned out pretty well. The flavor is distinctly understated, but the freshness from the herbs was nice as fall turns to winter. The slight licorice flavor from either the tarragon or chervil is definitely there. Perhaps it just needs a little heat to release its flavor. Chefs disagree on how much browning, if any, is ideal. Personally, I like more browning, both for flavor and the fact that it helps the egg unstick itself from the pan.

For each omelet, I used three eggs, beaten together with salt, pepper, and a tablespoon of milk. The herb mix contained three large parsley sprigs, minced, one minced scallion, and a teaspoon each dried chives, tarragon, and chervil. Half of the herb mixture gets added into the eggs before cooking. After melting about a tablespoon butter in a skillet over medium heat, the egg mixture is added to cook.

To make sure that none of the eggs end up runny, I like to tilt the pan and lift up the edges of the cooked portion, letting the uncooked egg flow underneath. After this, sprinkle the remaining herb mixture over the surface. When the top is almost set, fold the right and left thirds of the omelet over onto the center. If this doesn’t work and you end up with a half-moon shaped omelet, don’t worry about it, it will still taste good. Let the omelet cook for another minute, covering the pan if desired to help it set, then slide it onto a plate.

To make this simple mix of eggs and herbs sound extra fancy, serve with pommes de terre frits, compote de pomme, fruits frais, café au lait, or any combination thereof. In English, these are fried potatoes, applesauce, fresh fruit, and coffee with milk. To make anything sound fancy, say it in French, even if you have to use a translation app.

Make a one-time donation

Make a monthly donation

Make a yearly donation

Choose an amount

Or enter a custom amount

Your contribution is appreciated.

Your contribution is appreciated.

Your contribution is appreciated.

DonateDonate monthlyDonate yearly