1000 Foods (pgs. 288 – 289)

Imagine, for a moment, that you’re making stew on a cold day. It has beef, onions, carrots, celery, and parsnips, plus some butter and minced bacon to brown the meat and vegetables before adding liquid. Most people would think of adding potatoes at this point, and some cooks do, but they aren’t the key ingredient. That particular honor goes to grunkern, or green spelt. A specialty of Baden-Wurttemberg in the southwestern corner of Germany, the stew contains starch, protein, fat, vitamins, and flavor in one bowl.

Spelt is an ancient variety of wheat that’s been grown for thousands of years. The German word grunkern sounds very similar to “green corn,” because the grain is harvested before it’s fully ripe. In Europe, corn can mean any type of grain, not just maize and sweet corn. Exactly how green spelt was discovered is unclear. Perhaps one summer grain supplies were running low and the harvest was still a few weeks or months away, so some farmers harvested a bit of their grain early. Interestingly, grunkern doesn’t seem to be widespread in European cuisines. Maybe it was more popular before potatoes, which are also ready before the main grain harvest, were introduced from the Americas, but that’s just speculation.

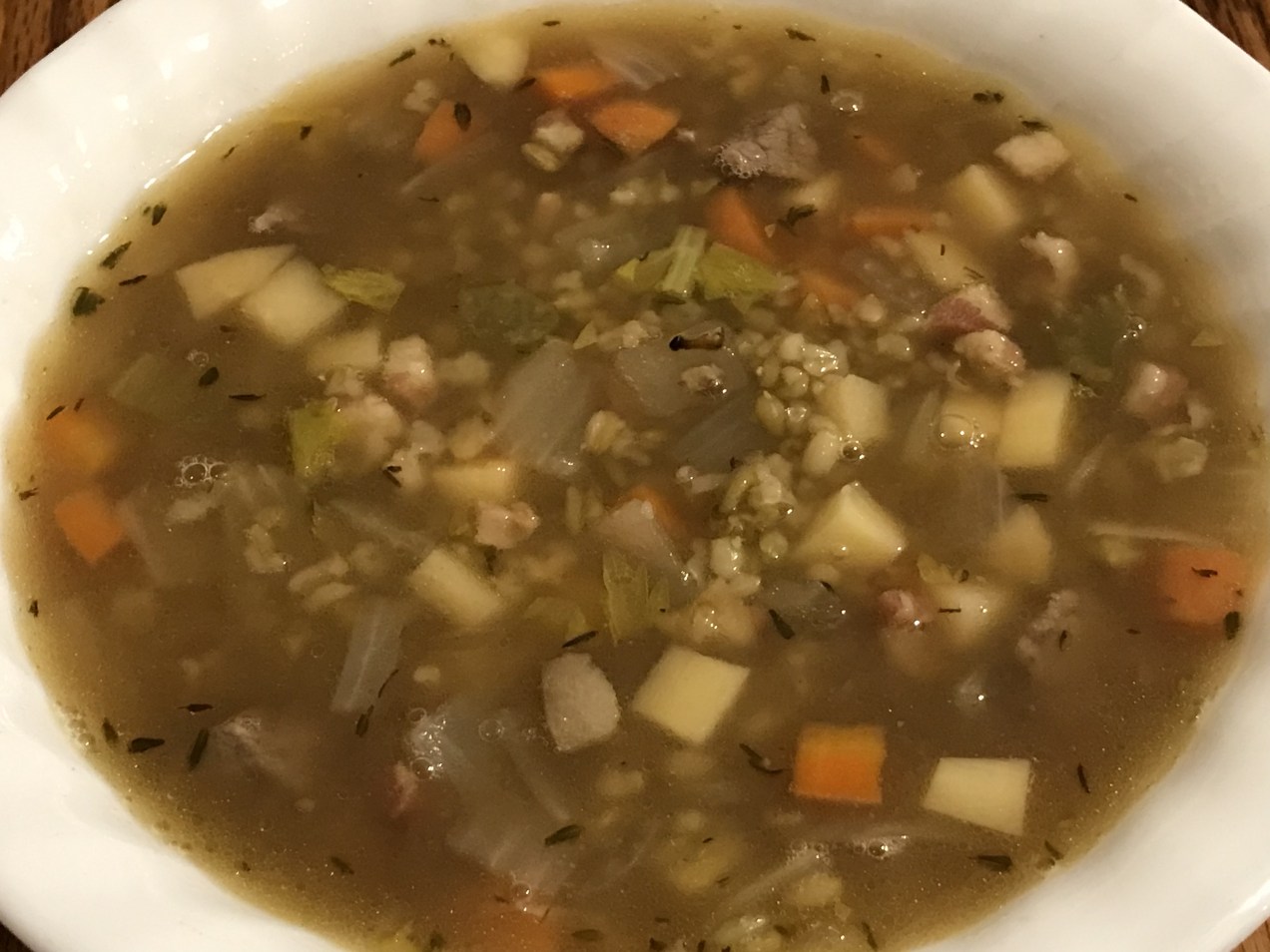

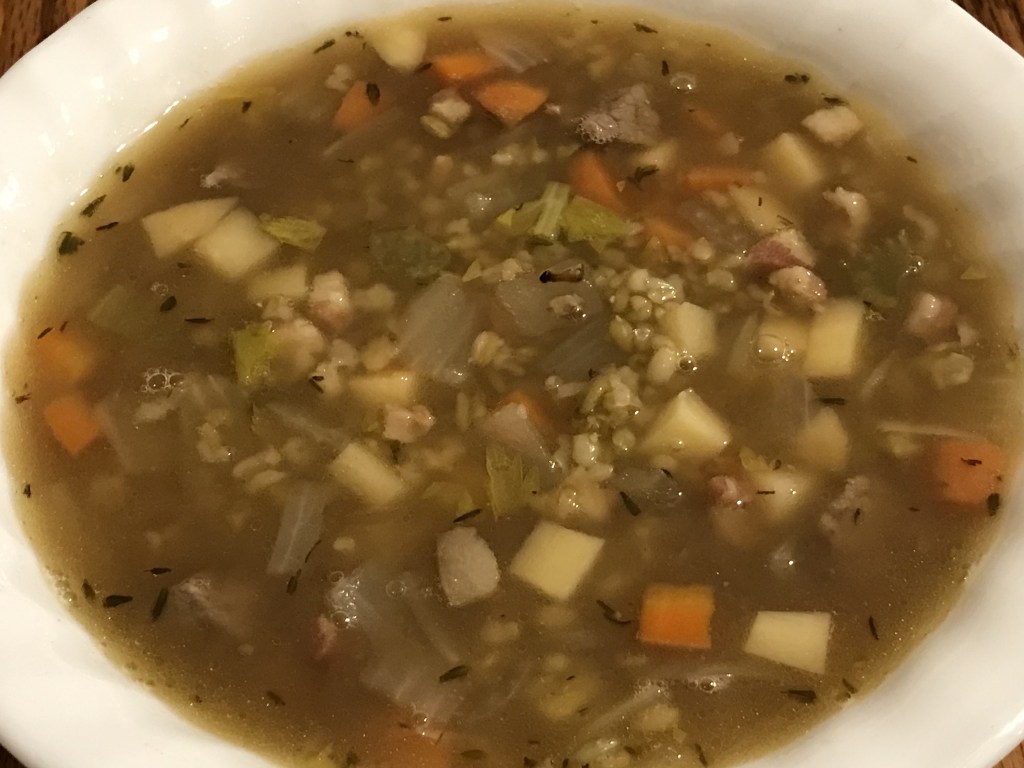

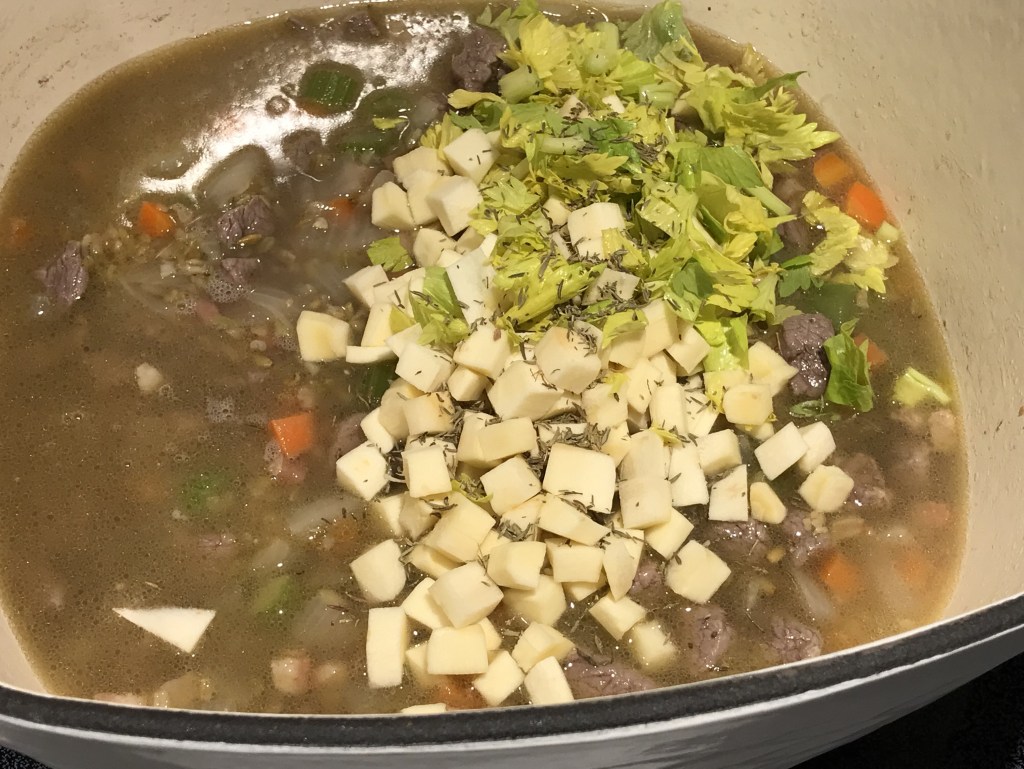

The full recipe can be found in 1000 Foods to Eat Before You Die on pages 288 – 289, but here’s a summary. Butter is melted on the stove, then bacon, onion, carrots, and celery are added. You can add the beef or pork at this point to brown, which I did. Then soaked grunkern is added, with optional leek and parsnip, along with celery leaves and the meat, if it hasn’t been added already. This is followed by a bit of thyme, pepper, and either broth or water. I omitted the leek but added a minced parsnip, celery leaves, dried thyme, and beef broth. The recipe called for salt, but that can be added later to taste. Since I used salted butter and broth instead of water, adding extra at this point was unnecessary. Then everything simmers for a little over an hour.

One thing that surprised me about this recipe was how little meat it uses. For 4 to 6 servings, it only called for 8 ounces beef or pork. That’s less than 2 ounces per serving, contrary to the stereotype of German food. Even though Germans have historically had more meat available per person that many other Europeans, large servings were an occasional treat, particularly during the Early Modern Era and into the 19th Century, after large-scale population growth and before industrial agriculture. So we have a stew with plenty of grain and root vegetables, with some beef and bacon as enhancements.

Overall, this soup is highly enjoyable. My favorite from this project is still beef-mushroom-barley, but this was an interesting change of pace. Like barley, the grunkern swells up in storage and upon reheating, so a bit of extra broth or water might be necessary. If you have trouble finding green spelt or grunkern, which I couldn’t find even online, try looking in a Middle Eastern food store. There it’s called freekeh, but the product is the same. Ziyad brand is one of the most widely available.

Next time there will be another soup recipe, so be sure to subscribe. Did I mention it’s free?